Published by Benoît Verzat on 24 February 2024

Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a quantitative method for evaluating the impacts of products or services that has been developed more than 30 years ago. This approach is used by hundreds of companies worldwide as part of eco-design initiatives, marketing campaigns, or environmental labelling. It allows to account for environmental impacts from the extraction of raw materials right through to the end of a product’s life.

This scientific approach makes it possible to sum up these impacts, relate them to a common scale (a “functional unit”), and thereby compare several products according to their environmental performance.

Therefore, LCA is the method at the foundation of the environmental labelling initiatives that have developed in recent years in Europe. The European Commission was preparing to publish on November 30 2022 a draft directive to outline the future regulation of environmental claims (“substantiating green claims”), of which environmental labelling is one axis.

Yet, the draft text ran into very strong opposition from consumer associations and environmental NGOs… so much so that its publication was postponed into 2023, without a precise schedule.

Giving consumers information so that each time they make a purchase they can choose a less-impacting product for the environment; quantitative environmental labelling based on LCAs … I was long enthusiastic about this idea! I conducted more than 60 LCAs, led eco-design projects, coordinated the creation of methodological reference frameworks for environmental labelling … and I changed my mind.

Generalizing environmental labelling of products relying only on LCA results is neither effective nor desirable.

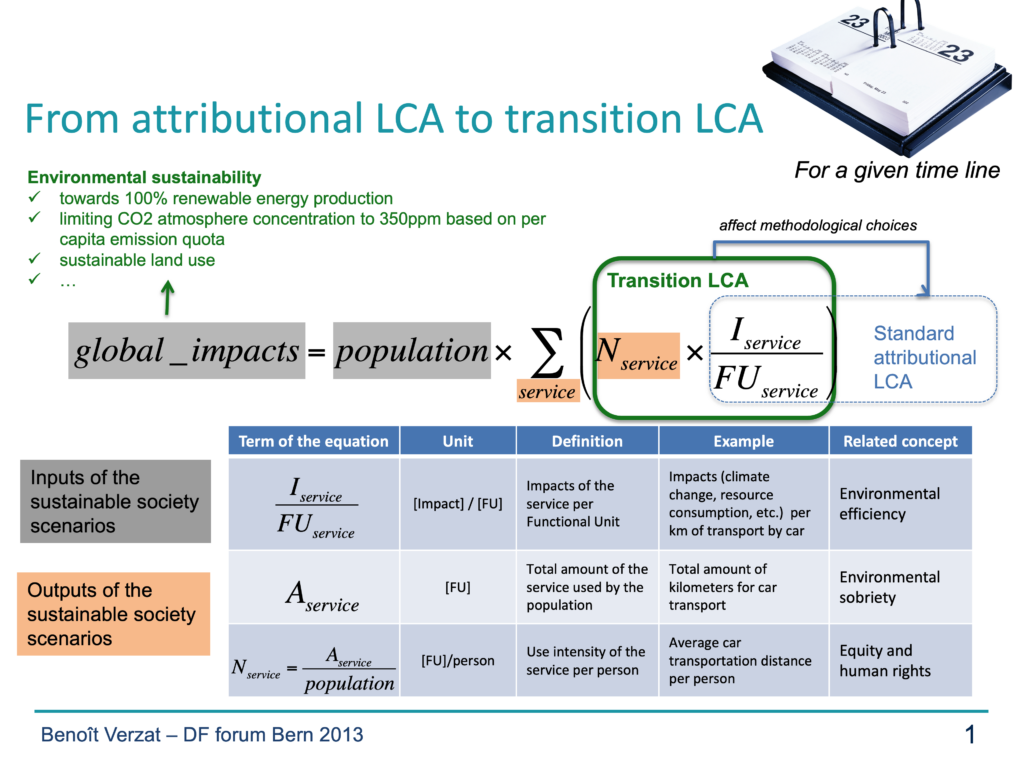

First, it must be emphasized that LCA focuses on a very limited portion of environmental issues: that of quantitative environmental efficiency. This is — per a functional unit (a quantitative measurement unit from LCA) — what are the environmental impacts.

Also, LCA appears to be totally irrelevant to address the notion of sufficiency, which rather questions the intensity of use of the studied product/service (how many times the functional unit is used). Sufficiency, yet, is increasingly recognized as fundamental to take the necessary measures to stay within planetary boundaries.

Moreover, LCA is more easily applicable to standardized, industrial, computerized processes: life-cycle stages are easier to quantify there. But these industrial standardized processes are often already systematically analyzed for economic efficiency. It’s therefore not surprising that this tool is more used by large industrial groups than by artisans, to promote the quality of their products.

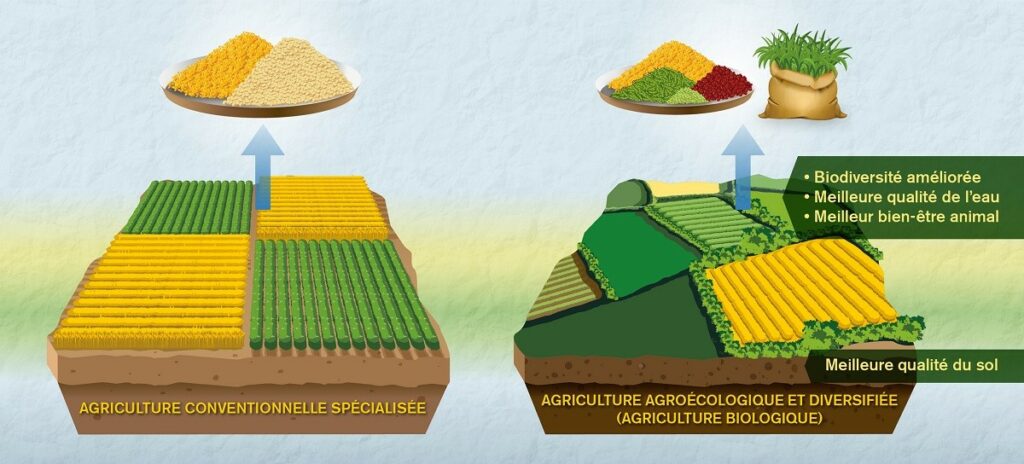

Finally — and the current methodology and practices of LCA are simply not sufficient to fairly evaluate the co-benefits of certain systems: for example, agroecology and organic farming.

Conventional farming produces higher yields, but organic farming offers other benefits. © Yen Strandqvist / Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden.

If environmental labelling based on LCA is not desirable, what should we do instead to encourage companies to reduce their environmental impacts? A better approach would be to generalize ecolabels. Indeed, if all the human and financial resources used for environmental labelling were allocated to:

- updating more regularly the criteria of the European ecolabel (which itself relies on LCAs),

- expanding the categories of products covered by this ecolabel,

- facilitating access for small producers to certification,

- systematically indicating on all non-labelled products that they are not certified,

- gradually legislating to ban products with problematic characteristics (dangerous substances, products from deforestation, etc.),

… then that would be much more effective!

In any case, the sum of individually environmentally efficient systems does not make a sustainable society. And LCA-based initiatives focus on improving systems taken individually.

LCA is a useful and powerful tool to understand environmental issues and ask the right questions. But if LCA results are not interpreted considering societal scenarios aligned with planetary boundaries — like those proposed by the négaWatt Association or Solagro — they don’t enable defining actions consistent with those limits.

This measured use of LCA is precisely the one I share with my students and clients!